Still Lifes in Canadian Art

Madison Beale | November 22, 2023

Did you know there is more to still lifes than what meets the eye? In this blog post we look at the beginnings of the still life genre and how it has been used in Canadian art.

Still Lifes in European Art

Popularised during the 17th Century across what is now the Netherlands and Belgium, the genre of still lifes flourished as markets and trade routes expanded but may predate the Italian Renaissance. A new mercantile class in the Lowlands with disposable income and shifting religious beliefs desired art that reflected the power of Dutch and Flemish trade in a deceivingly modest manner. This contrasted the tastes of the Spanish empire that had recently been ruling the area. The Spanish broadly preferred opulent, didactic works that dramatised Catholic beliefs and classical mythology. As the Dutch shifted from Catholicism to Calvinism under new leadership, collectors wanted austere works that venerated the new Dutch Republic, which often resulted in landscapes, church or genre scenes and bountiful tabletop still lifes boasting Dutch produce or foods that had been imported from new colonies.

Flowers are especially associated with the still life genre. A tulip, or any flower, is a subtle way to signify the transience of life; the blooms are ephemeral and are to be appreciated for a short while. In the Dutch Republic in the 17th century, tulips also signified wealth, since they were incredibly expensive at this time. Artists also created vanitas paintings, where objects like skulls, instead of produce, reminded viewers of their mortality and to lead virtuous lives. The skull is an example of a memento mori, Latin for “remember you must die”. Flowers can also communicate this in a subtle manner; the fragility of a delicate, impeccably rendered petal and the tension created as it falls upon an intricately laid out table reminds the viewers of precisely what they cannot take with them.

As it developed, the still life genre became a locus for innovation as well as a way for an artist to display their technical skill. For the few women artists who were able to receive formal training at this time, still lifes were seen as one of the only appropriate subject matters for a woman to paint. Ariane van Suchtelen, curator for the Mauritshuis in the Hague, remarks that women artists were relegated to still lifes because their contemporaries believed they could not conceptualise grand history paintings, nor was the subject matter and manner in which they would need to learn anatomy appropriate for women. Artists like Rachel Ruysch and Clara Peeters were recognized during their lifetimes as well as now as some of the most exquisite still life painters from that era.

Still Lifes in Canadian Art

Many artistic conventions from Europe were brought over to Canada. As time went on, still lifes became an indispensable part of an artist’s training in Europe as well as North America by the 19th century. Mary Dignam, a preeminent figure in the history of art in Canada and for women’s art in particular, painted sublime still lifes among other important works. Mary Dignam paved the way for women artists in Canada when she formed the Women's Art Association of Canada in 1887. In this untitled still life painting, Dignam is aware of baroque still lifes, as evidenced by her use of chiaroscuro (Italian for "light-dark, referring to the contrast of light and dark in a work of art) with a dark background emphasising the illuminated flowers. Dignam’s use of contrast combined with loose, impressionistic brush strokes demonstrates a robust understanding of art history combined with technical skill. The wilting flowers call back to early still lifes that both showed painterly skill and a desire to convey a deeper message about life.

Though best known for landscapes, many members of the Group of Seven painted still lifes during their careers, such as J.E.H. MacDonald and Franklin Carmichael. In Leaves and Flowers, MacDonald paints autumnal flowers and foliage in front of draped white fabric. The flowers rest in a white vase with a blue rim and bend gently towards crunchy maple leaves. This work is loose and uses thicker strokes of paint to develop the folds in the fabric background. Carmichael’s still life is more experimental, moving beyond a tabletop scene by showing plants on a windowsill flanked by curtains looking out to a house and sky. Carmichael’s rectilinear paint application conveys a sense of calmness and structure in the work.

Working with shading, spatial rendering and realism, still life sketching is an invaluable part of an artist’s formal training. William Kurelek’s studies of objects helped him create his masterworks of Canadian life, especially his more pastoral or agricultural scenes. Kitchen in a Poor Home in 19th Century Podilia is one such example. Kurelek uses crosshatching to depict spatial recession and the volume of objects laid out on a kitchen table. Its use of negative space prompts the viewer to fill in these gaps in their imagination, aided by the inference of floral wallpaper or decor. The viewer can feel the pride the inhabitants take in their home, situated on the border between Ukraine and Moldova. The kitchen is empty - a viewer may wonder the significance of such emptiness partnered with Kurlek’s title referencing both the 19th century and the region. Is the scene empty because someone was called to the door while cooking, or does this blankness evoke something darker? The bleakness of the scene may infer that the house was empty in the wake of pogroms in the area during the 19th century. Alternatively, it could also reference an abandoned home following the first wave of Ukrainian immigration to Canada. Kurelek’s family was from Bukovyna, a province bordering Romania and close to Podilia. The Ukrainian and Jewish diaspora were frequent themes in Kurelek’s work and may help a viewer contextualise this particular still life study.

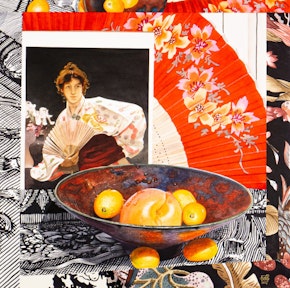

Vivian Thierfielder's watercolours are luxuriously intricate and often reference art history in their composition. With impeccably rendered fruit in her paintings, Thierfelder often uses the imagery of old masters and famous works from the 19th century to compliment her compositions. The background is made up of many patterns that seem discordant, almost collage-like. The space in which the bowl inhabits is illogical and perspective is skewed, creating an uncanny atmosphere.

In The Red Fan (2007), Thierfelder draws inspiration from the 19th-century European fascination with Japanese art, also known as Japonisme. As trade routes between Japan and France became stronger, Europeans were very interested in the country's culture and began importing prints, furniture and clothing. The woman seen behind the bowl of fruit (which may be referencing imported Raku Ware) is a replication of Charles Sprague Pearce's 1883 painting Lady with a Fan, which depicts a European woman dressed in a Kimono. The use of a reproduction in the painting may also call back to other important works from the Japoonisme period, like Edouard Manet's Emile Zola (1868) in which Manet depicts reproductions of Japanese prints and his own work, Olympia (1863). In borrowing the visual language of Japonisme, Theirfelder comments on contemporary cultural and technological exchanges that can happen in art to this day.

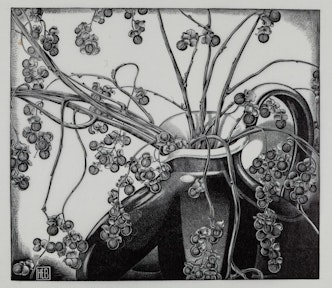

Another still life that borrows from motifs in Japanese art is Henry Bergman’s Untitled (Still Life Flower Vase). Working in monochromatic wood engraving, Bergman focuses on the depth that can be achieved with shading. Bergman was increasingly interested in plant studies in his work from the 1930s onwards. The swirling floral stems protruding from the vase suggest inspirations from the Aesthetic movement from artists like Aubrey Beardsley, whose work Bergman may have seen reproduced in magazines like The Studio.

Taking the time to analyse and make sense of not only what the artist might be telling us, but what we think about the work and its symbols expands our understanding of still lifes. This still life by William Goodridge Roberts defies traditional academic standards of spatial rendering and is indebted to Paul Cézanne's rejections of such rules in his respective still life paintings. William Goodridge Roberts strays from convention in a genre that originally intended to replicate a semblance of reality. A darkness enshrouds the table while orange hues peek through bluish tones in both the background and bouquet of flowers. Who may have been sitting at the table?

Still lifes are rich works packed with symbolism for viewers to unpack. They offer us moments for pause and contemplation in our busy lives. These paintings may seem superficial, but looking closer at these works reveals deeper truths about ourselves and cultures around the world.