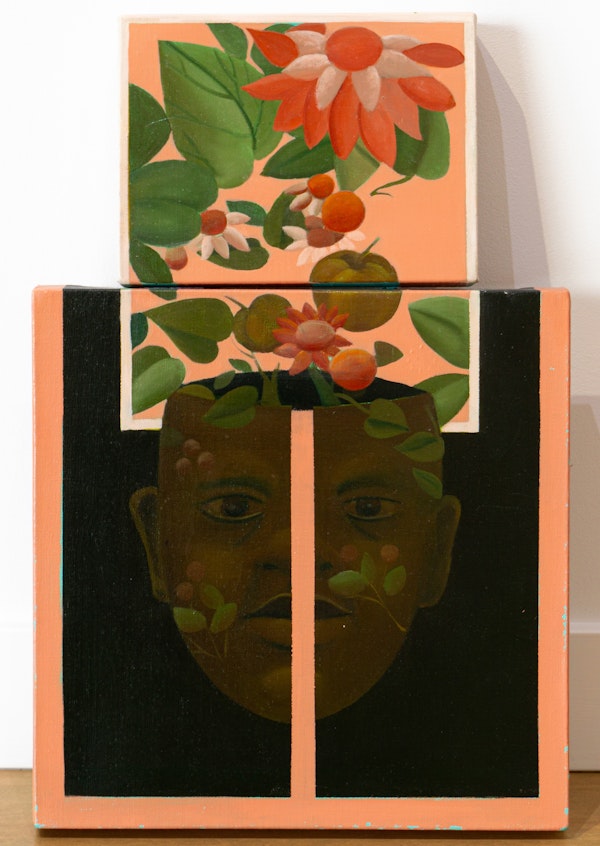

Faces

On Hold

Esther Warkov

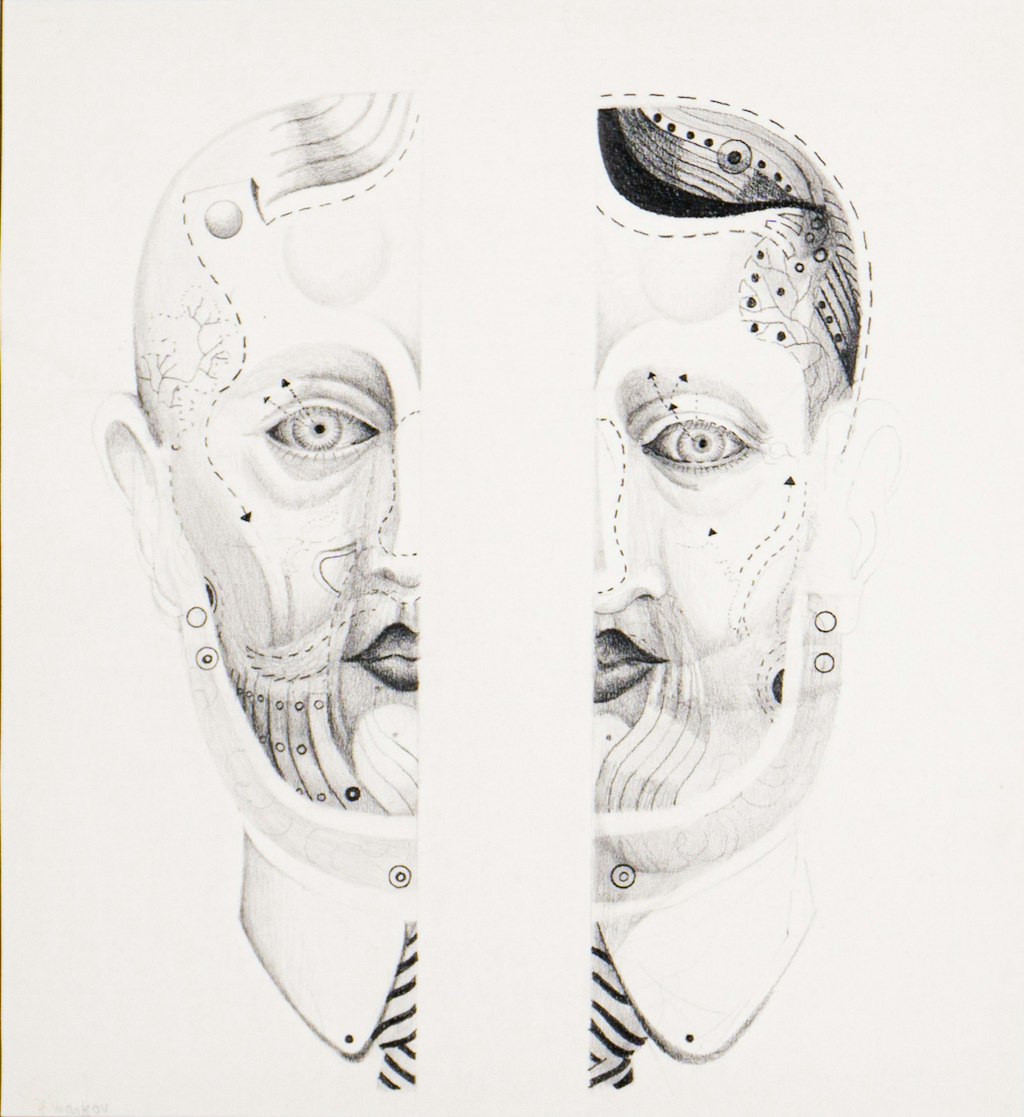

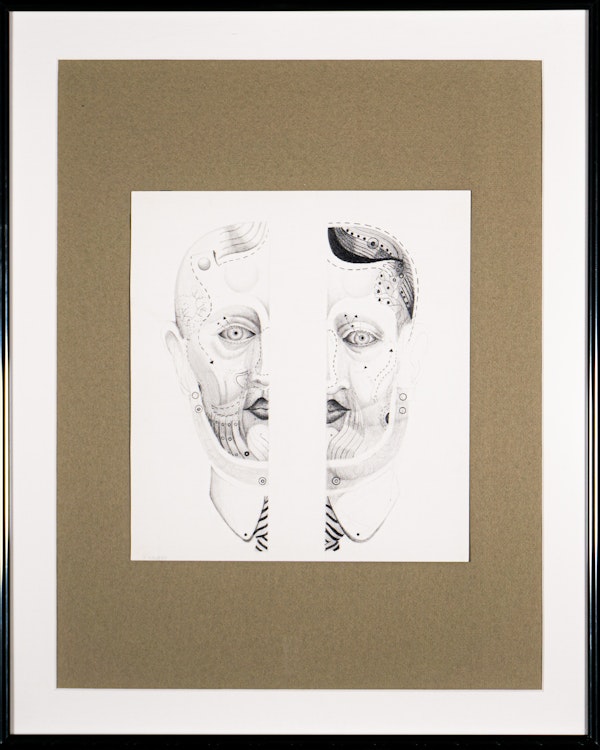

Esther Warkov (born 1941) is a Canadian artist. Warkov is known for her paintings that invoke a fantasy world in their imagery. Warkov was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba. From 1958 to 1961 she studied at the Winnipeg School of Art.

Her work is included in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada and the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

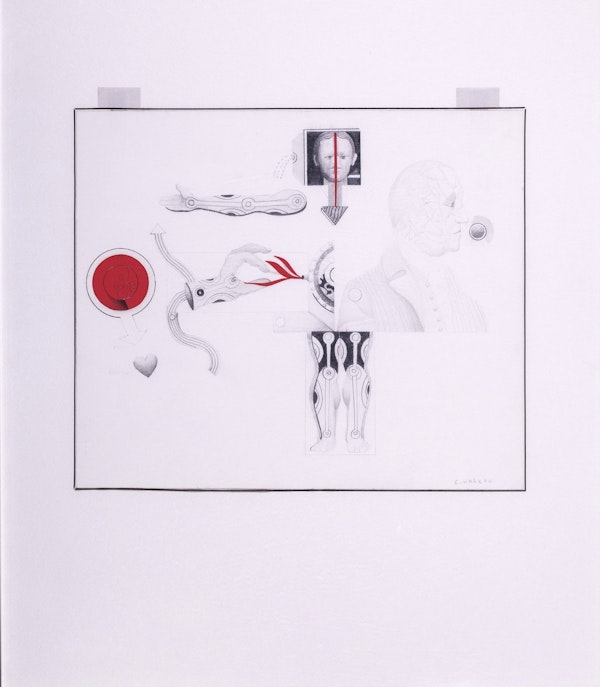

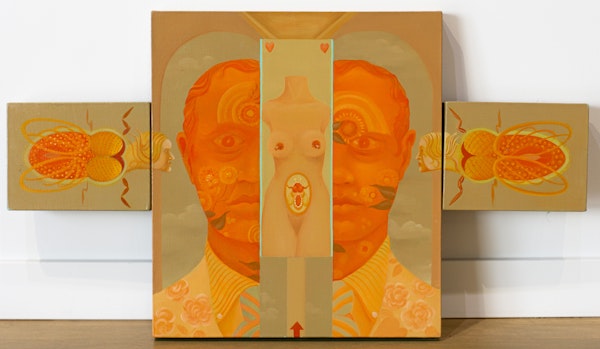

Subtly psychedelic, Warkov's stylized motifs reveal the influence of the Eastern European community into which she was born. Her motley scenes integrate a recurring and morphing array of images—townsfolk, historical figures, insects, and engine parts—appropriated from the old photographs, postcards, medical textbooks, and department store catalogues the artist scavenged from local junk shops and second-hand stores.

Warkov’s refreshingly idiosyncratic paintings engage with matters of race, ethnicity, social history, and cultural memory. At the same time, her work does not correspond to specific intentions, revealing no coherent stories. “When most people look at my work,” Warkov told Maclean’s in 1977, “they want to know what the symbolism is—and the truth is I don’t have any.” In the absence of an encompassing narrative, Warkov invites the viewer to meander, as one might through a found box of nameless photographs, and simply revel in the partial, provisional, and ultimately inarticulate strangeness of her painted worlds.

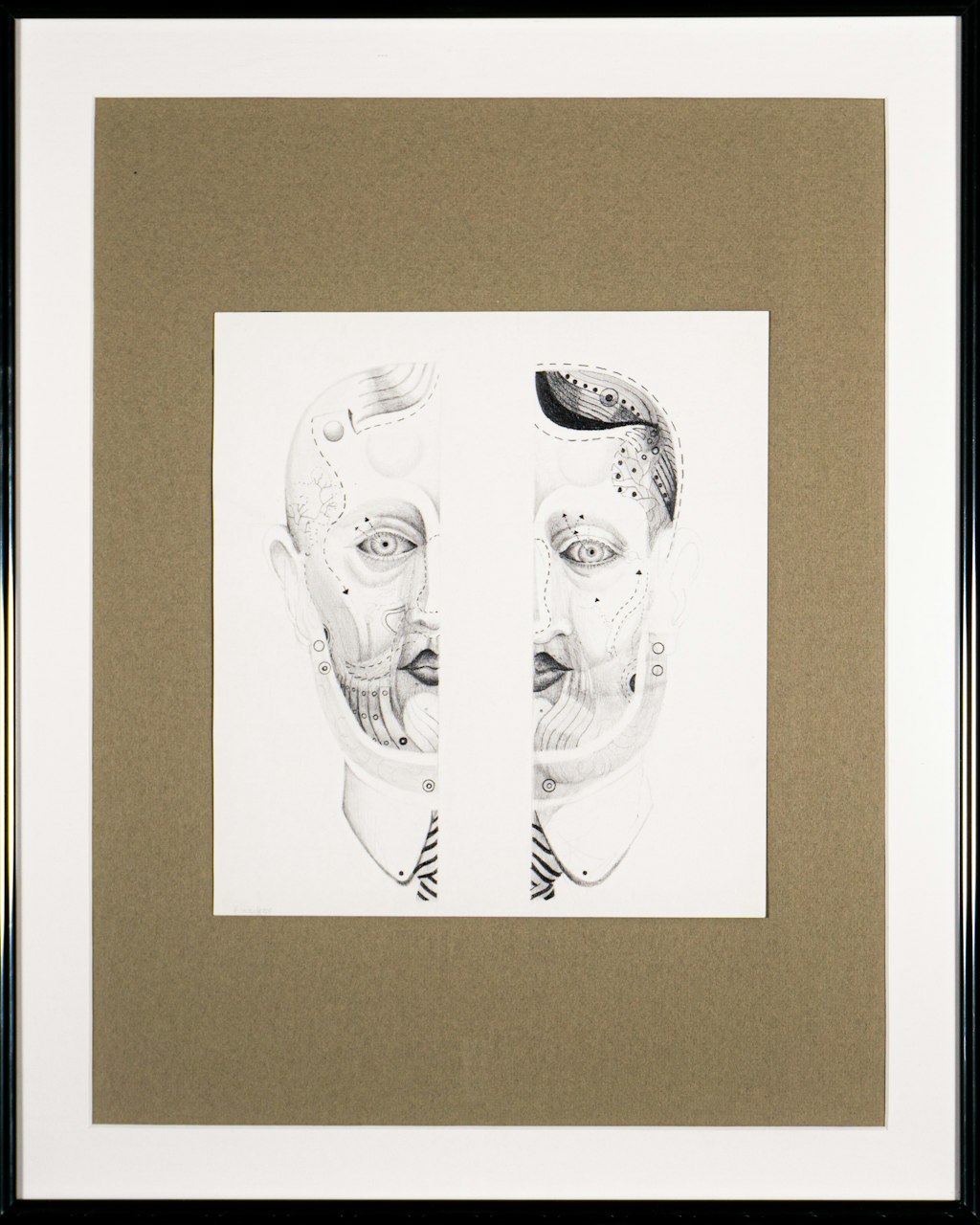

Esther Warkov

Esther Warkov (born 1941) is a Canadian artist. Warkov is known for her paintings that invoke a fantasy world in their imagery. Warkov was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba. From 1958 to 1961 she studied at the Winnipeg School of Art.

Her work is included in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada and the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Subtly psychedelic, Warkov's stylized motifs reveal the influence of the Eastern European community into which she was born. Her motley scenes integrate a recurring and morphing array of images—townsfolk, historical figures, insects, and engine parts—appropriated from the old photographs, postcards, medical textbooks, and department store catalogues the artist scavenged from local junk shops and second-hand stores.

Warkov’s refreshingly idiosyncratic paintings engage with matters of race, ethnicity, social history, and cultural memory. At the same time, her work does not correspond to specific intentions, revealing no coherent stories. “When most people look at my work,” Warkov told Maclean’s in 1977, “they want to know what the symbolism is—and the truth is I don’t have any.” In the absence of an encompassing narrative, Warkov invites the viewer to meander, as one might through a found box of nameless photographs, and simply revel in the partial, provisional, and ultimately inarticulate strangeness of her painted worlds.