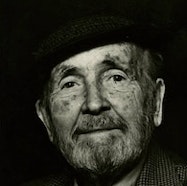

Untitled Portrait

Sold

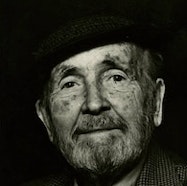

Nicholas de Grandmaison

1892 - 1978

Order of Canada, RCA

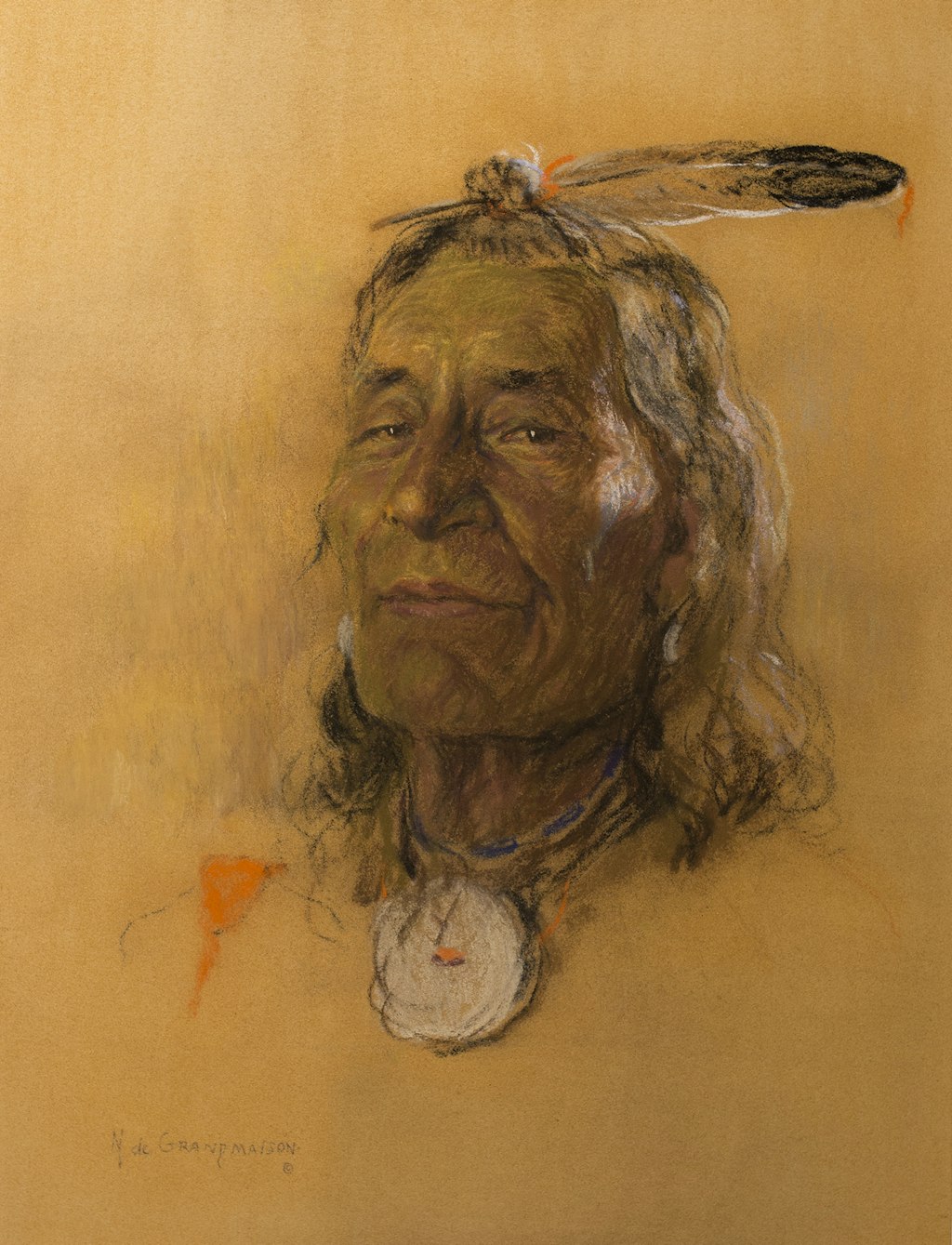

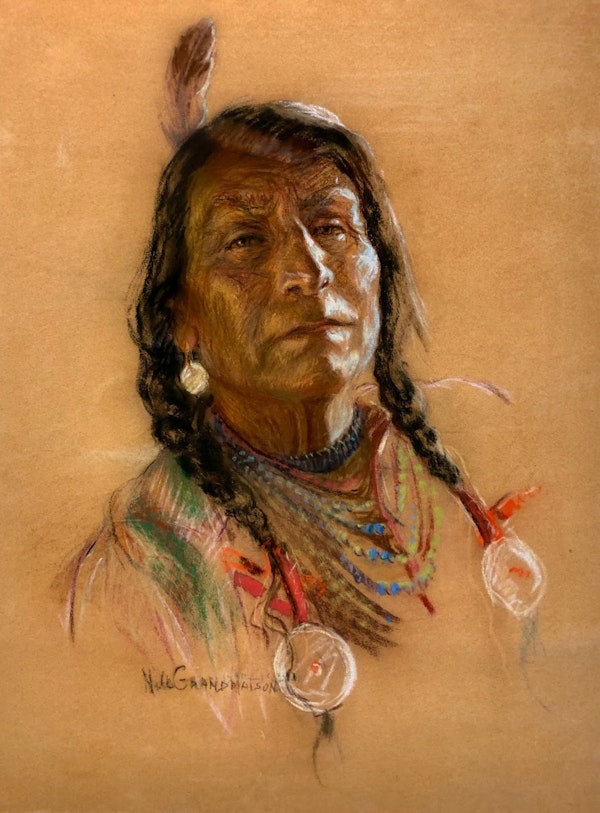

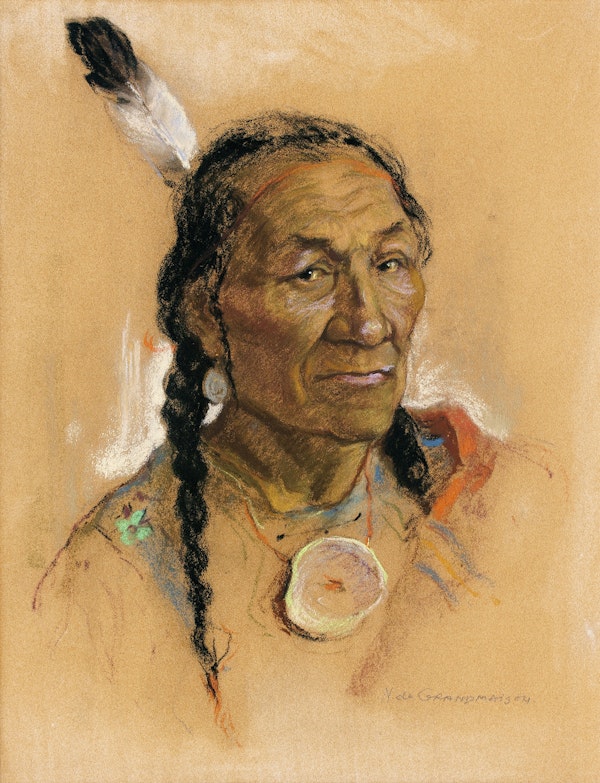

Nicholas de Grandmaison was inspired by the people around him, seeing their stories reflected in the lines on their faces. Towards the end of his career in 1964, he remarked that he had a preference for older sitters because young people “have not lived enough or suffered enough to have interesting faces.” He became renowned for his portraits of the Indigenous peoples of North America, and particularly those of Western Canada.

His artistic inclinations developed as a young man in pre-Bolshevik Russia. His father had fled France for Russia, orphaned by the revolution. He settled in Tsarist Russia and joined the military, as did his sons when they came of age. Nicholas followed suit by enlisting in the army and was made a sub lieutenant. He was captured during the Battle of Tannenberg in 1914 and spent four years as a prisoner of war. In prison, de Grandmaison passed time by drawing and completing portraits of fellow prisoners and guards.

Following the end of the war and de Grandmaison’s release, the wives of his fellow high-ranking soldiers sponsored the artist to travel to London and attend the St. John’s Wood School of Art. However, he did not establish himself in London and instead emigrated to Canada as a farm worker. Finding little success in agriculture, he began working at a printing and engraving firm in Winnipeg and completed portraits on the side. His first major commission came in 1926, when the Law Society of Manitoba asked de Grandmaison to paint the portraits of many influential justices in the province.

The stock market crash of 1929 had a detrimental effect on de Grandmaison’s investments and overall financial stability, yet he abandoned a steady paycheck to become a full-time portraitist. In 1930, he took a transformative trip to The Pas, Manitoba, where he encountered the Indigenous people that lived on Treaty 5 territory. Upon returning to Winnipeg, de Grandmaison enjoyed relative success with his new body of work. Due to unfavourable economic conditions, commissions were infrequent. Since the portraits of the Canadian Indigenous people sold well, de Grandmaison was able to continue painting.

After his trip to The Pas, he found himself enamoured with Indigenous peoples and their ways of life. He travelled around North America depicting the Indigenous peoples of the areas he visited. He was thought to be mad by many of the communities he visited because his behaviour was erratic and he was known to be irritable. As he became more confident in his style, his portraits became looser and built upon a foundation of unorthodox colour and shading rather than lines with oil pastels. His portraits focus on the sitter’s unique facial features and nods to their heritage in their clothing, but he rarely identified his subjects by name. Often his sitters sport feathers in their hair, braids and culturally significant jewellery. He endeavoured to portray his subjects with pride and regality, not wanting to depict them as victims. Nicholas de Grandmaison framed his subjects with the negative space around them with only stray lines reaching out into the space and emphasizing their faces.

In 1972, Nicholas de Grandmaison was awarded the Order of Canada. Later in his career, Charlie Crow Eagle gave Nicholas de Grandmaison the title of honorary chief and the name Enuk-Sapop, meaning Little Plume. The artist was buried on the Peigan Reserve in Alberta, Treaty 7 territory, where the turning point of his career began.

Nicholas de Grandmaison

1892 - 1978

Order of Canada, RCA

Nicholas de Grandmaison was inspired by the people around him, seeing their stories reflected in the lines on their faces. Towards the end of his career in 1964, he remarked that he had a preference for older sitters because young people “have not lived enough or suffered enough to have interesting faces.” He became renowned for his portraits of the Indigenous peoples of North America, and particularly those of Western Canada.

His artistic inclinations developed as a young man in pre-Bolshevik Russia. His father had fled France for Russia, orphaned by the revolution. He settled in Tsarist Russia and joined the military, as did his sons when they came of age. Nicholas followed suit by enlisting in the army and was made a sub lieutenant. He was captured during the Battle of Tannenberg in 1914 and spent four years as a prisoner of war. In prison, de Grandmaison passed time by drawing and completing portraits of fellow prisoners and guards.

Following the end of the war and de Grandmaison’s release, the wives of his fellow high-ranking soldiers sponsored the artist to travel to London and attend the St. John’s Wood School of Art. However, he did not establish himself in London and instead emigrated to Canada as a farm worker. Finding little success in agriculture, he began working at a printing and engraving firm in Winnipeg and completed portraits on the side. His first major commission came in 1926, when the Law Society of Manitoba asked de Grandmaison to paint the portraits of many influential justices in the province.

The stock market crash of 1929 had a detrimental effect on de Grandmaison’s investments and overall financial stability, yet he abandoned a steady paycheck to become a full-time portraitist. In 1930, he took a transformative trip to The Pas, Manitoba, where he encountered the Indigenous people that lived on Treaty 5 territory. Upon returning to Winnipeg, de Grandmaison enjoyed relative success with his new body of work. Due to unfavourable economic conditions, commissions were infrequent. Since the portraits of the Canadian Indigenous people sold well, de Grandmaison was able to continue painting.

After his trip to The Pas, he found himself enamoured with Indigenous peoples and their ways of life. He travelled around North America depicting the Indigenous peoples of the areas he visited. He was thought to be mad by many of the communities he visited because his behaviour was erratic and he was known to be irritable. As he became more confident in his style, his portraits became looser and built upon a foundation of unorthodox colour and shading rather than lines with oil pastels. His portraits focus on the sitter’s unique facial features and nods to their heritage in their clothing, but he rarely identified his subjects by name. Often his sitters sport feathers in their hair, braids and culturally significant jewellery. He endeavoured to portray his subjects with pride and regality, not wanting to depict them as victims. Nicholas de Grandmaison framed his subjects with the negative space around them with only stray lines reaching out into the space and emphasizing their faces.

In 1972, Nicholas de Grandmaison was awarded the Order of Canada. Later in his career, Charlie Crow Eagle gave Nicholas de Grandmaison the title of honorary chief and the name Enuk-Sapop, meaning Little Plume. The artist was buried on the Peigan Reserve in Alberta, Treaty 7 territory, where the turning point of his career began.