Form A Line

Sold

Sean William Randall

Growing up between Regina and Winnipeg, Sean William Randall believes the Prairies did not easily lend itself to a traditional environment for an artist to emerge from. He came of age surrounded by records and a burgeoning but somewhat isolated artistic community preoccupied with Modernism. While in the classroom, Randall could be found sketching in the margins of elementary notebooks, chided by teachers who would later encourage the artist to pursue his art.

Randall traversed the stone aisles of Flemish churches and bountifully laid tables by the old masters through the pages of hefty art books in public library collections. Reproductions of works by Holbein and Dürer fascinated the young artist; the luminosity of Holbein’s paintings and Dürer’s incredible attention to detail are facets that characterise Randall’s work today.

While at university, Randall was able to develop his technical skills but found the rigid academic approach to art stifling. Looking back, the artist recognises that his architectural training grounds his practice in academic conceptions of composition and perspective but diverges from those expectations.

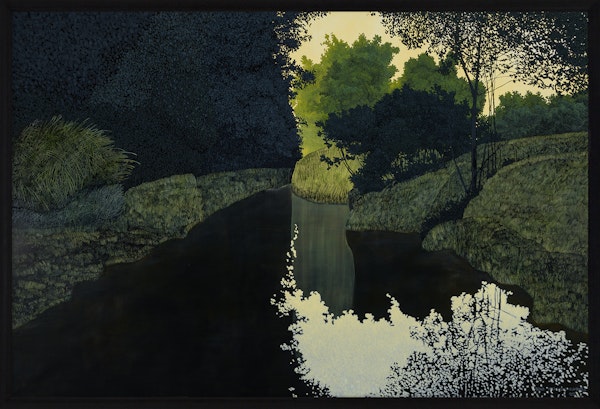

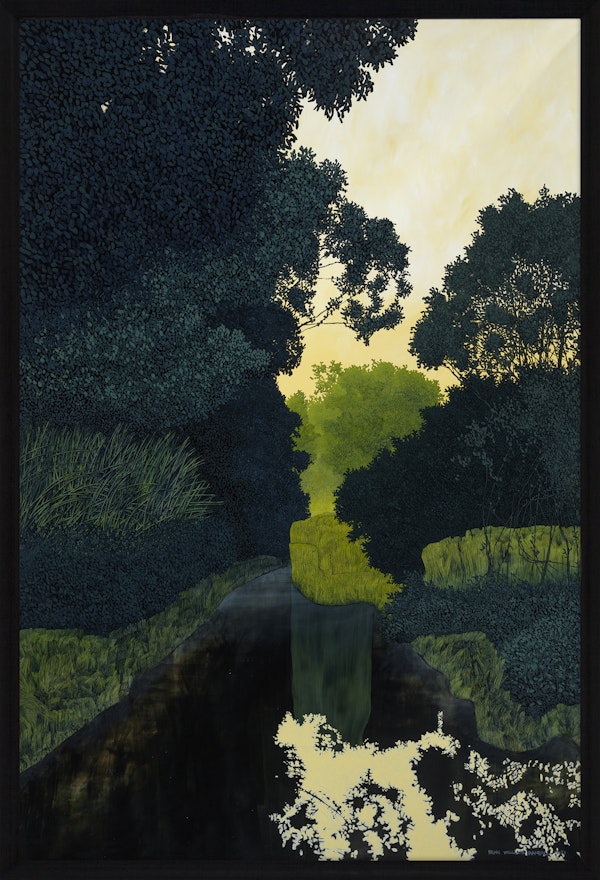

The artist’s interest in landscapes can be traced back to being Canadian and inspired by varied, awe-inspiring nature, he believes. Randall’s landscapes, however, are not immediately recognizable as distinctly Canadian. Instead, Randall seeks to give the land personality and emotions through the use of light and composition that is not necessarily realistic. In his work, Randall strives to create a sense of intimate isolation. His landscapes are uninhabited and uncanny, evoking a sense of eerie liminality. It is in this respect that Randall believes his viewers see what they wish in his works, backing away from any definitive answers as to what they may be about. Even when his work is figurative, his subjects ignore the viewer and operate entirely within their worlds. Whether these figures are aware of the viewer’s presence is irrelevant because this is how they see us. We are merely onlookers, entirely transient and invisible in these dreamlike spaces.

Above all else, Sean William Randall is meticulous when it comes to his work. Often working - and reworking - his paintings, he takes a holistic approach to his art. As a result, his paintings become autonomous, guiding entities. Often, there is a key colour that Randall anchors his paintings with, as everything from composition to orientation of the canvas changes. Every painting Randall makes inevitably influences his future works. Motifs are borrowed from past series that are reinvented into new, heightened contexts.

Randall’s work is collected in significant public and private collections around the world, perhaps most notably in the MacDonald room at the Canadian Embassy in London, England. Works of steel public art conceptualised by Randall are also found around Canada. The artist is excited to explore ambitious new subjects and compositions in bodies of work in the future.

Sean William Randall

Growing up between Regina and Winnipeg, Sean William Randall believes the Prairies did not easily lend itself to a traditional environment for an artist to emerge from. He came of age surrounded by records and a burgeoning but somewhat isolated artistic community preoccupied with Modernism. While in the classroom, Randall could be found sketching in the margins of elementary notebooks, chided by teachers who would later encourage the artist to pursue his art.

Randall traversed the stone aisles of Flemish churches and bountifully laid tables by the old masters through the pages of hefty art books in public library collections. Reproductions of works by Holbein and Dürer fascinated the young artist; the luminosity of Holbein’s paintings and Dürer’s incredible attention to detail are facets that characterise Randall’s work today.

While at university, Randall was able to develop his technical skills but found the rigid academic approach to art stifling. Looking back, the artist recognises that his architectural training grounds his practice in academic conceptions of composition and perspective but diverges from those expectations.

The artist’s interest in landscapes can be traced back to being Canadian and inspired by varied, awe-inspiring nature, he believes. Randall’s landscapes, however, are not immediately recognizable as distinctly Canadian. Instead, Randall seeks to give the land personality and emotions through the use of light and composition that is not necessarily realistic. In his work, Randall strives to create a sense of intimate isolation. His landscapes are uninhabited and uncanny, evoking a sense of eerie liminality. It is in this respect that Randall believes his viewers see what they wish in his works, backing away from any definitive answers as to what they may be about. Even when his work is figurative, his subjects ignore the viewer and operate entirely within their worlds. Whether these figures are aware of the viewer’s presence is irrelevant because this is how they see us. We are merely onlookers, entirely transient and invisible in these dreamlike spaces.

Above all else, Sean William Randall is meticulous when it comes to his work. Often working - and reworking - his paintings, he takes a holistic approach to his art. As a result, his paintings become autonomous, guiding entities. Often, there is a key colour that Randall anchors his paintings with, as everything from composition to orientation of the canvas changes. Every painting Randall makes inevitably influences his future works. Motifs are borrowed from past series that are reinvented into new, heightened contexts.

Randall’s work is collected in significant public and private collections around the world, perhaps most notably in the MacDonald room at the Canadian Embassy in London, England. Works of steel public art conceptualised by Randall are also found around Canada. The artist is excited to explore ambitious new subjects and compositions in bodies of work in the future.